Ursula Pike Interview

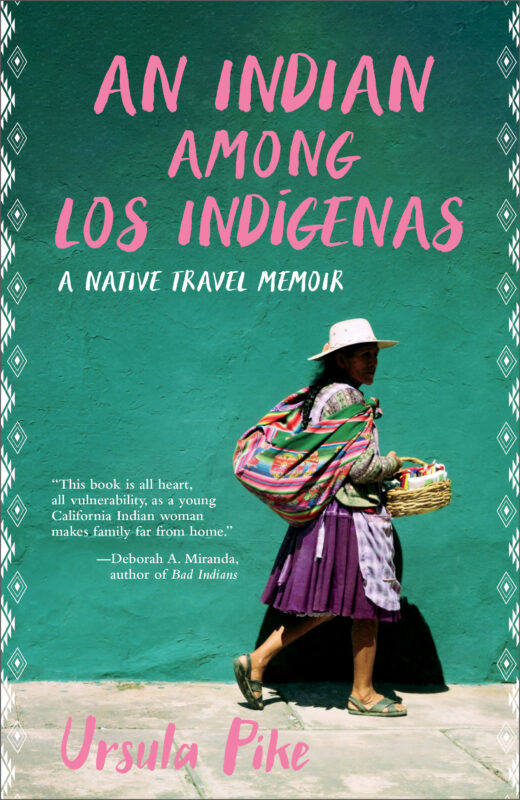

Anita Roastingear and Ursula Pike met as classmates at the Low Residency Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in Creative Writing Program at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). They were part of the second cohort of students in the newly created MFA program. Anita and Ursula focused on Creative Nonfiction. Pike’s debut memoir An Indian Among Los Indígenas: A Native Travel Memoir was published by Heyday Books on April 6, 2021.

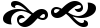

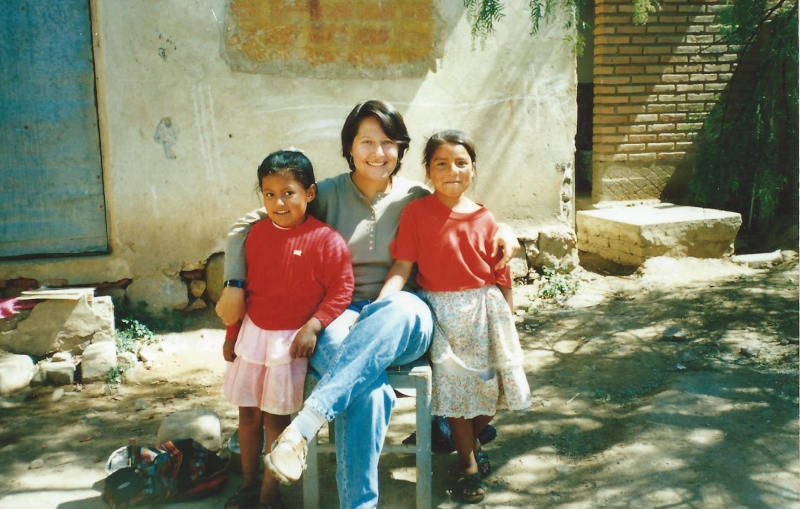

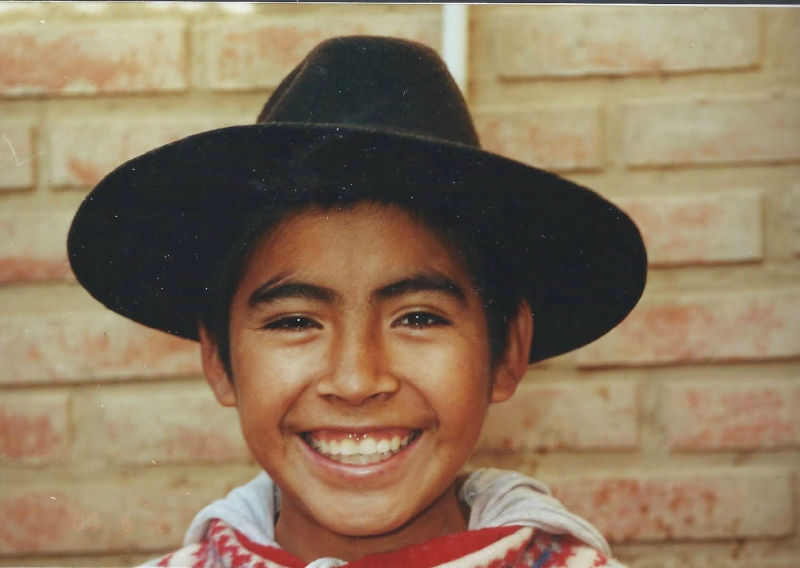

Questions by Anita Roastingear; photos from Ursula Pike.

Once you completed your tour of duty in the Peace Corps, there must have been memories which made you feel like an ambassador to the cause. Can you share one which you addressed in the book but didn’t elaborate on?

It is interesting that you called my Peace Corps time my tour of duty. You are a veteran and I’ve heard other veterans use that term. I am reminded that Native Americans serve in the military at rates that far outnumber our percentage of the population. That’s not the case with Peace Corps. I don’t know the number of Native Peace Corps Volunteers because the organization only reports the total percentage of “minorities” (34%) but it remains small.

My feelings about the work I did in Bolivia are complicated. From the moment I arrived, I could see that Bolivians didn’t need my help or guidance. If I was lucky, I might learn something from them. The one project I wasn’t conflicted about was starting a bakery with the teenage girls at the Children’s Center where I was stationed. It was a collaboration between me, the girls, and a staff member at the Children’s Center who helped me.

If I’m an ambassador for anything it is for the knowledge I learned while working on these projects. Before I went to Bolivia, I thought I was supposed to show up with great ideas and make them happen. That’s the assumption at the heart of the white savior approach to helping people. Working with the kids and the staff of the Children’s Center taught me that projects don’t work and won’t last without genuine collaboration at every step. All projects needed to start and end with the community, had to start with the kids. The bakery project didn’t last beyond one semester. At the time, the outcome made me feel like a failure. But truthfully, I learned how not to start a project. The following semester, the teenagers at the Center started their own project which was smaller in scale and manageable. I did very little in that second project. But that was good because they weren’t relying on me for anything.

Our world in the States has changed dramatically. Joining the Peace Corps must have changed as well. What do you not tell young people about joining the Peace Corps?

I tell them almost everything. I may not get into the specifics of my most self-destructive behavior, but I let them know it was a difficult experience. For many Returned Volunteers, their years of service were two of the most exciting of their lives and they remember them with great fondness. I like to let potential volunteers know that the experience is also complicated, especially for volunteers from communities that have been marginalized in the U.S. They may be the only person like them in their group or community. But the awareness they will bring to the experience is why they should volunteer.

The Peace Corps has been impacted by the Black Lives Matter protests and calls for equity and diversity like other agencies and organizations have been. The organization has official Peace Corps Diversity Recruiters. I hope my story can be part of the agency’s reflection on what they might need to change. There is a group of Returned Volunteers calling for defunding the Peace Corps for many of the same issues I wrote about in my book. I am not part of that group, but I support taking a hard look at the way development and service have been approached by the Western world.

I am sometimes asked by a Peace Corps recruiter to participate in a panel discussion on my experience to potential volunteers. I let the recruiter know that I will be honest about my experience. The recruiters so far have been fine with that. That is smart because it was a volunteer who was honest with me about her experience that motivated me to apply. I attended an event where a woman told me the first volunteer position she was placed into was not what she wanted to do. Her story was the first time I had heard a complicated and imperfect story about the experience. She told me she fought for a better, more interesting position and was able to get reassigned. Once I was in Bolivia, I knew volunteers who did exactly that. I didn’t need to move but if she hadn’t shown me that everything wasn’t perfect all the time, I’m not sure if I would have applied.

Speaking of change due to COVID-19, how will you promote your book and how do you feel about the demise of the face-to-face book tour?

Those of us with books coming out in 2021 are challenged but are lucky compared to the authors who had a book published in 2020. I attended online readings early in the shutdown where neither the audience nor the authors were sure what to do. My heart goes out to those authors who struggled to unmute themselves or were Zoom-bombed. Now most of us have experience with virtual events and are comfortable being on camera.

My book launch and every reading I have scheduled will be virtual. I will miss being able to talk to people, to shake someone’s hand and thank them for buying the book. But virtual events also mean my mom in Oregon and my aunt in California will be able to attend. That never would have been the case for face-to-face events. I also had concerns about the accessibility of in-person events. Tiny bookstores with narrow aisles or limited disabled parking made me wonder if I could hold the event in a location where people in wheelchairs would feel welcome. With a virtual event, that’s not an issue.

A year of attending virtual events and classes has also taught me that as authors, we can engage with our audience more than simply reading from the page. We can take what we’ve learned about being better online instructors during the lockdown and apply that to readings and other book events. The best online instructors engage their students but also find ways to get students to engage with each other. These are the same elements of the best virtual reading events. I’m trying to incorporate some of that into my virtual events. I’ll let you know how it goes.

The creative writing classes I took at Austin Community College were the first I ever took. I was embarrassed to show anyone else my writing and registered for an online class. It changed my life because I was able to learn craft and the other students told me what they did and didn’t like about my writing. One audience I would like to connect to are students at community and technical colleges. There seems to be an assumption that community and technical colleges are only for people to become automotive technicians - and that is definitely something you can do at those colleges. In the drive to make everyone a skilled employee in a high-demand job, we forget that there are people who don’t want to become full-time writers but who still want to learn how to tell stories. To me, the personal narratives by writers who are computer programmers or automotive technicians are some of the most interesting I’ve read.

I felt emboldened and curious about your affair with a married man who was the father of young children. It was titillating and I wondered how many times you revised it or even thought about deleting it all together. What prompted you, as an indigenous woman, to be so open about your own humanity?

In 2014, I was given the following prompt, “Write about an emotional crime you committed.” I had been trying to write about my experience in Bolivia for many years but most of what I wrote seemed superficial or resembled a recruitment brochure for Peace Corps. I wanted to write about the difficult and contradictory truths of what actually happened while I was there. The prompt asking for an emotional crime showed me a way forward. Maybe the relationship wasn’t a crime, but the prompt helped me examine my role in what happened.

As a reader of memoirs and creative non-fiction, I am drawn to complicated narratives full of imperfect people because that’s what I am. I wanted to show the full messiness of my humanity. Of course, I wondered what people would think of me after reading about my experience. Ultimately, I knew the whole truth had to be in the book if I was going to write it. I changed the names of all of the real people in the book and obscured identifying details to respect their privacy. The examples set by writers like Elissa Washuta and Deborah Miranda who write honestly and thoughtfully about their lives encouraged me to be truthful and bold.

Titillating! Ha, that’s perfect. Intimate scenes are some of the most difficult to write because they are emotionally charged. I was very lucky to have feedback from Melissa Febos, one of my mentors at the Institute for American Indian Arts. She writes powerful and compelling intimate scenes and helped me see when I had gone too far or not far enough.

As an indigenous author from a federally recognized tribe, do you intend to write within the realms of other genres? If so, which genre will that be? I am thinking of your link to the land and your tribe. Will you write an historical novel concerning your people? Maybe interview your tribal members and write something for young adults?

I do see a need for a book like that, but I don’t know if I’m the one to write it. I feel most comfortable writing creative non-fiction. Luckily, there are many Karuk writers publishing everything from children’s books to academic books. The success of Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz’s great book An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States is evidence to me that there is a hunger for books by Native writers about our history.

To me, the most interesting stories are the recent histories of my and other tribes. The things they are doing right now to improve the lives of their tribal members and communities. I think about how well many tribes handled COVID-19 vaccinations. My mother was able to get her shot in Oregon at a neighboring tribe’s health clinic. Many Native people were vaccinated quickly and efficiently thanks to the healthcare workers on reservations. I am in one of Texas’ largest cities and have no idea when I’ll get my shot. I have seriously considered getting in my car and driving north to Oklahoma because the Cherokee Nation has done such a fantastic job of vaccinating both Native and non-Native people in their area.

For my next book, I’m working on a series of essays about my experience teaching English as a Second Language at a chicken processing plant in Mississippi. I was a contract worker without health insurance and when I discovered I was pregnant, my aunt suggested I go to the Indian Health Clinic run by the Mississippi Band of the Choctaw Indians near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The doctors and nurses saved me and my baby. I don’t know what I would have done without them.

For some of us, acquiring a literary agent is like capturing a mythical being. Can you give us a glimpse of your publishing adventure for new authors? Did you consider self‑publishing?

Getting published is a daunting process and, honestly, if you’re a woman of color trying to publish your first book in your extremely late 40’s, it can feel impossible. I kept waiting for an agent to hand me an “Advanced Maternal Age” brochure like the ones I received when I was pregnant with my first child at 36. “Are you sure you want to start doing this now, at your age?” they seemed to be saying.

In Austin where I live, every year there’s an Agents and Editor’s conference held by the Writers League of Texas. The first time I attended, I was overwhelmed and spent most of the time hiding in the corner sweating. I could barely admit that I wrote a book, much less try to sell it to a stranger in 30 seconds. While I was completely unsuccessful at that conference, the experience forced me to develop a clear and concise description of my book. For the first time, I began to think about what might make someone want to buy the book. That put me on the road to developing a book proposal which I eventually sent to Heyday Books.

I never considered self-publishing, but I have friends who have and I understand the lure of that approach. What I didn’t know until I attended the Agents conference was that I could approach a small publisher directly or that there are a multitude of options for publication. Small presses can give you incredible support and take care of the difficult work of publishing. I’ve met writers publishing really amazing work with small presses. University Presses are also putting out interesting work like the beautiful poetry book by our friend Mar Ka from the University of Alaska Press. Hybrid presses are another option as are publishing contests. My only suggestion is to be aware that you have options. You’ll be doing a lot of work revising and promoting your book regardless of who your publisher is, so be prepared.

Heyday Books is a small press out of California that published wonderful and important books like Deborah Miranda’s Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir. I sent them my book proposal and was happy when they asked to read the whole manuscript. Their response to the book was warm and supportive. The editors at Heyday specifically understood that the book wasn’t telling a story about one specific organization or even one tribe, but rather about the implications of being an indigenous woman in an international context. I knew I’d found a home.

When we were at IAIA, the instructors told us most books take years to get published. I remember feeling disheartened because it had taken me years to get to that point. But the editing process was helpful and, once I recovered from the shock of seeing the multiple pages of revisions they’d requested, it was, dare I say, fun. The time and effort my editors put into revising made the book better but also made me a stronger writer.

Finally, it was intriguing to read about your re-visit to the country of Bolivia. Why did you feel the need to return with your husband in tow?

I was so excited to visit Bolivia because although I’ve stayed in touch with many of the friends I made there, I wanted to see for myself what Bolivia is like now. Bolivia has changed significantly since I lived there 20 years ago. In 2006, they elected their first Indigenous president—Evo Morales. He ushered in massive social and economic changes. There are paved roads where before there had only been dirt, there are basketball courts in rural communities where none had existed before, and students were learning indigenous languages in school. Not everyone loves Evo, and I wanted to ask people what life under Evo had meant for them. I also wanted to talk to indigenous Bolivians about their understanding of what it means to be Quechua or Aymara now. I wanted to see if the word indio (indian) was still a bad word for Bolivians. It is but indígena isn’t.

It was also important to be reminded of the way Bolivians speak. My book has many recreated conversations. Being in Bolivia and listening to my friends talk and joke reminded me of how they speak. After returning, I read through the dialogue in the book and revised conversations that weren’t realistic.

My husband came with me because he was also a volunteer in the Peace Corps in Bolivia. He came in a group of volunteers who arrived the year after I did. As a white man, he had a different perspective and different experience. I found it interesting to see how he interacted with Bolivians and if it was different. We were also able to visit the town where he lived and meet the children and grandchildren of the Bolivians he had worked with. For both of us, our time in Bolivia was a significant experience and while it was starkly different, it remains an important part of who we are.

But, truthfully, I will always go back to Bolivia. It is an amazing country and I love returning every few years to see what has and hasn’t changed. Some people think we live in a homogenized global world where everything everywhere is the same. When I travel to Bolivia, I’m reminded that isn’t the case. There are striking differences and the joy of traveling is experiencing the variety and diversity of the cultures on our planet.

An Indian Among Los Indígenas: A Native Travel Memoir is now available from Heyday Books.

Anita Roastingear is a Cherokee Nation citizen and associate professor of arts and humanities at Navajo Technical University. She has an M.F.A. in Creative Writing - Nonfiction from the Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Culture and Arts and an M.A. in English Creative Writing from Northern Arizona State University.

Ursula Pike is an enrolled member of the Karuk Tribe and Associate Director of the Digital Higher Education Consortium of Texas. She has an M.F.A. in Creative Writing - Nonfiction from the Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Culture and Arts.

Other Works

Damien Ark Interview

by Matt Lee

... I want people to understand the complexity of what sex addiction feels like and also how confusing sex is to a survivor of sexual abuse ...

2 Poems

by Joel Allegretti

... A bat flaps through / an open window / of a country home ...