Mahdis Marzooghian Interview

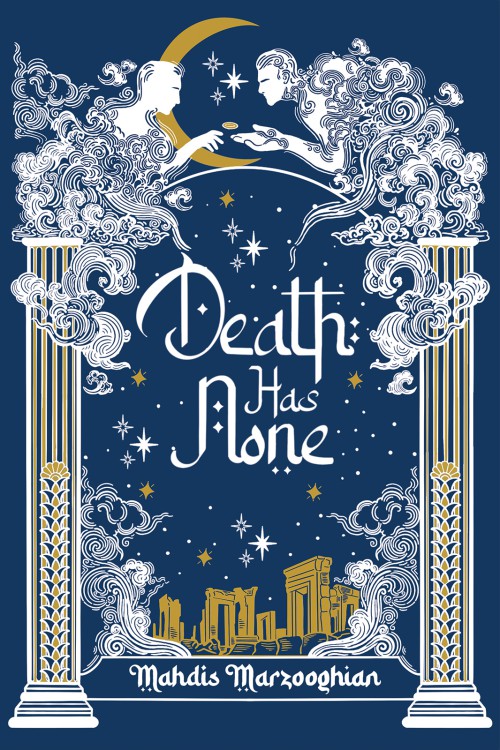

Mahdis is the author of Death Has None (Austin Macauley Publishers, 2023), a novel exploring cultural duality and the significance of reputation, loyalty, family, and values. When an unspeakable tragedy strikes the Nezami family, fifteen-year-old Cyrus is left to piece together the true story or risk losing everything he has ever loved.

I meet Mahdis to talk in that dismal week between Christmas and the new year. She is pure gold on a crowsong evening. We sit at the bar of a small sushi restaurant in North Bethesda, and though the place is full near to capacity and there is a classical playlist opining to us from behind the bar—Swan Lake and Beethoven’s Fifth and the like—it is quiet enough to talk.

Death Has None is available from Amazon and other publishers.

You’re generally a writer of nonfiction. You work in financial editing, and you do a lot of your own work in nonfiction. Have you always wanted to write a novel? What inspired you to write Death Has None?

My love for creative nonfiction started when I was in graduate school at Towson [University]’s Professional Writing program and taking Angela Pelster-Wiebe’s course. She was all about nonfiction writing; her class was actually on writing the memoir. I remember I just fell in love with that genre, and I felt like I had a lot of interesting things to say as far as culture goes—you know, growing up in the United States with two different cultures. So I started just writing, and it was cathartic, in a way, because you’re remembering all these memories and writing about them in this nice, narrative way. So I fell in love with creative nonfiction in grad school.

When I started working in the professional world, it was all financial editing and press releases—you know, like, very dry stuff. But I’d always wanted to write a novel, [it is] like every writer’s dream. And back in 2017, I started getting ideas for these characters, this narrative that was sort of structured around my own experiences as an immigrant growing up in the U.S. But also, I also wanted to create these characters that were going through something completely fictional.

I’m fascinated by Persian history, so creating this character, Cyrus, whose father is a storyteller and also intrigued by Persian history made me think Why not use the stories of Cyrus the Great to frame this tragedy they’re going through as a family?

So, I don’t know! It kind of all just came together. I actually remember typing a lot of it during my downtime at work, like, I would have my Google Doc up and I’d just be typing away.

A lot of Cyrus’ memories are my memories. It was really fun, actually, writing from the POV of a fifteen-year-old who is so different from me and sort of injecting into him my own memories and bits of my personality.

This book is built on stories passed from father to son at crucial, if tragically early, moments. Were you interested in writing into the tradition of embedded narrative, stories within stories, or did it come naturally? Were you always interested in these stories?

Before my research of Cyrus the Great, I actually hadn’t known most of what I had written about—how his grandfather wanted him killed as an infant, for instance—I had no idea! So awful.

I did want to structure [the plot] inside the framework of a larger story and sort of match the pacing to the mythos of this historical figure.

There are hints in the book that Sohrab, the father, gives Cyrus, the son, that are kind of like foreshadowing; for instance, he says “Even blood can’t prevent your own family from betraying you,” or something along those lines. But Sohrab didn’t really know. It was this unconscious feeling that he had.

I do leave the story open-ended for the character of the father. Sohrab didn’t know what his brother was or wasn’t capable of. He never wanted to manifest that into reality. He never wanted to believe it because it was too horrible, but he does show these little hints of awareness through his stories, Cyrus’ stories.

When the book opens and this tragedy befalls his family, Cyrus is relatively young, still working on his own story, so to speak. It’s hard enough to be a teenager—someone who is trying to figure out who they are—without so heavy a burden, so great a namesake. Now, Cyrus is also the narrator of the story, and his internality is incredibly journalistic, as if he himself is taking up the mantle of reporter, attempting to offer up an unbiased account of his own mother’s death. This contrasts sharply with the beautiful metaphors and Farsi idioms which his family begins heaping upon him when he begins asking tough questions. He’s a fact-finder, as suspicious of allegory as he is drawn to it by blood.

Of course, just because something is allegorical doesn’t mean it’s not the truth. Cyrus realizes this as he learns more about his family’s culture, the culture in which he was raised, and how those often disparate things collide violently in his father’s case. Can you speak more on this split between the “factual” and the “truthful” and how these concepts seem less and less separate as Cyrus ages?

I think that’s such a great observation. You know, this terrible thing has happened, and who is prepared for such a thing? He lost his mother in the blink of an eye and now people are dancing around him, only telling him things in snippets. He’s a young teenager, of course they’re not going to bluntly tell him everything. So—I like how you put it—he’s needfully journalistic; he goes on a hunt. He takes his parents’ letters without his father’s knowledge. He’s looking for clues. He’s searching for anything that will give him answers. He’s trying to figure out how it’s possible that this man he’s known and loved as his father—someone who he’s respected, admired, whose stories have helped him grow up into the person that he’s become so far—could do something like this. And obviously, that’s going to make anyone feel like they have to be paranoid. They can’t trust anybody because this person that they’re closest to has done something that is horrific.

So he goes on a personal journey trying to figure it out. He begins reading between the lines of his father’s stories and, in doing so, becomes more capable of deciphering what it is that his family is telling him.

The idioms are things he has heard ever since he was a little boy but never understood the meaning of. [Over the course of the book,] though, he grows beyond his age. He’s forced to grow up quickly—he suddenly becomes the man of the house, he has to shield his five-year-old brother from things he himself is too young for—and this makes him understand things that most people would not grasp until perhaps their twenties or thirties. He realizes: Oh, these things my mother would tell me about respect… or Oh, that story my father always told me… now I understand, because I too am facing these terrible things.

It's the same with the stories. A lot of what I put in about Cyrus [the Great] are true accounts. But then, that story with the coin? I created that, both because I thought it worked well in the story and because it fit Cyrus the Great’s character, you know, as someone to whom justice and honesty were very important. That was a story that I created, as well as certain moments between he and the queen. That’s another thing—when Cyrus says in the story that he couldn’t really find a lot of information on Cyrus the Great, that was my own experience. In the research that I did, I found accounts of war and various battles, but stuff about him? I know that it was thousands of years ago, like, I understand that—

[Laughs]

—but I really tried to find more personal accounts of his life, things that would give you a closer look into the kind of man that he was, the kind of personality that he had. Obviously, the historical and political stuff is important—I mean, he did a lot of great things—but I wanted to make [Sohrab’s stories] this intimate look into who Cyrus really was.

I like that. Some people might scoff at the idea of invented stories, but when someone is, you know, great enough, or old enough, or far enough back in the depths of history, their mythos just keeps being built by those that come after them. Even those petty stories that you hear from friends get exaggerated over the years. Millennia can both magnify details and lose them entirely. So I think it’s super interesting that you have not only created a story to tell people, but that you are actively writing into that history.

Thanks!

You mentioned pulling from both research and personal experience in the writing of Death Has None. I’m curious about the mix of those two sources. How much of the novel came from your personal experience or family tradition? How much came from research? Did you speak to anyone in your family—parents, grandparents—when it came to questions of culture or family history?

I didn’t really interview anyone—not it a formal way, anyway. I would just always ask questions. Like, anything I was working on at the time, I would ask my mom or whoever was available, you know. Or if there was a certain idiom that I wasn’t 100% on, I’d ask, Is this right? or Am I saying this correctly?

And there was this added difficulty of writing everything out in Finglish. Farsi has its own alphabet, and it’s actually read from right to left. I couldn’t put that into the novel, so I had to rely on Finglish. I had to write it all out in English; I had to write the Farsi out in the [Latin] alphabet. The formatting was really important to me, too, in that sense. Anything that was in Farsi, I’m sure you noticed, was italicized, and then the English came after in quotes to clarify the meaning of the expression.

So those were most of the things that I would fact-check with my family. But the research was multifaceted. It wasn’t just history; it wasn’t just my own memories. There was also the research—and this was the hardest part of the book—on the courtroom, and the trial, and the law, and oh my goodness, the procedures.

You had to make sure you didn’t miss anything, right?

That was probably the hardest part! I can’t tell you how many weird things I googled—and I was paranoid, you know! I’m looking up something really specific regarding murder… You know, like, I’m a writer, don’t come after me! And then, I have one friend who’s a lawyer, but she’s not even in criminal law! She used to be in divorce law and is currently a lawyer for the public housing sector in New York.

So I would ask her questions like If they say this, then what? and I would check with her on the language like If they were to say this, is this correct?

But I didn’t want to get too clinical with the trial, either, because it wasn’t the main aspect of the novel. It was only a couple of chapters that were important, right, but it wasn’t the heart of the novel. I wanted it to be very authentic to Cyrus’ point of view. Even though he grows up to be a lawyer, at the time he’s talking about the case, he’s a fifteen-year-old boy. There’s actually a line where he says: “A lot of the things they said and did went over my head.” I put that in there deliberately. And honestly, that helped save my ass as a writer, because if there was something that maybe I missed…

It’s the point of view!

It’s the POV!

He’s fifteen!

You can’t come after me!

So that kind of worked out really well.

But still—yeah, I can’t tell you how much I just googled really random, weird things about the law. And it also had to be Virginia law, because the story takes place in Virginia. It was so specific. That was probably the toughest part.

I was actually having this conversation with that friend who’s a lawyer, and she was talking about Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, which I haven’t read yet, but she loves. She was telling me about a note at the beginning of the book where [Garmus] mentions that she had an actual chemist as her consultant for all the terms and things she referenced in the novel. And then my friend told me that she was on Goodreads one day—you know, trolling the comments for the book—and that she was astounded by how many negative comments there were from people saying that it was just all wrong. And Garmus had a consultant!

You can’t win! Even with a major publisher, a New York Times Bestseller…

Anyway, my friend was saying all of this to tell me—because I was being really hard on myself at the time—that you don’t have to be an expert to write a book. And I think that’s very interesting: when you’re writing about something and it’s very technical, and it’s part of a field that you don’t have any expertise in, but you still have to write about it in a very authentic way… How do you balance that?

I think you did a great job of it. The choice of narrator really doesn’t hurt—

It doesn’t!

Now—I want to throw a direct quote your way. Keeping in the theme of things we don’t really know much about—

[Laughs] Yeah, go for it!

“Loss is the greatest life lesson, because death, the most certain of all things, teaches us about it.”

I love that line. I love that line, and I think it rings so true, especially because, as a global population, we have been dealing with such an incredible number of highly visible tragedies and losses of life in the past couple of decades, and yet at the same time we are also increasingly attempting to distance ourselves from death. Of course, this is coming from a Western perspective (which is slowly infecting the world…)

So, with that quote in mind and loss being one of the most profound things we as humans can experience, what are your thoughts on the sanitization of death? Does the stark distance we create between the living and the dead make each death into a tragedy?

It’s awesome that you made this note of how differently death is treated. It is so sanitized here. I grew up here [in the United States], but the first time I experienced death in my family, I was seventeen years old, and we had actually gone to Iran over that summer. My grandfather was really sick at the time, and he ended up passing while we were there. The funerals there are different than a funeral you would go to here. Witnessing the pain—it was my mother’s father—seeing her absolutely sobbing at the cemetery… There was no “be quiet, be respectful.” No. The pain is very out there for everyone to see. That was a culture shock for me because I had never seen something like that until then.

There are also different burial traditions. In the Muslim tradition, you put the body in a white shroud before lowering it into the grave. I stood off to the side then because it was hard for me to see my mother in that state, and it was all a little too overwhelming.

Another thing in regards to how death is handled in Iran is the high honor held in particular deaths. Being a martyr, dying for your country… Martyrs who died during the Iran/Iraq War are still very much glorified. There are tons of streets in Iran named after soldiers who died during the war.

So martyrdom is a very big part of the culture, and death is very much out there.

Another tradition I describe in the book is marking the death of someone who has passed. Once seven days have passed, you have a ceremony, have the close family come over, mourn, and remember the lost person. And then, there’s also the fortieth. And then there’s the one year. These are marked days where you actually have a ceremony, everyone wears dark clothing, and there are different desserts served that are representative of mourning. In Western culture, you obviously wear black, and there are some similarities that cross over, but [in Iran] it’s not as—I like that word—sanitized. There’s no expectation to mourn quietly. You’re commemorating the dead, actively remembering them. In the book, there’s also the photo that [Cyrus] describes of his mother with the black ribbon around it; that’s also very much a part of it. You have a photo of [the deceased] just sitting on a mantle or on a table for at least the year so that everyone can see them there. I know sometimes that reminder is painful, but I think the difference is that we’re not afraid to feel that pain. There’s not so much distance.

So it’s more about sitting with the pain than asking Well, how can I fix it?

Exactly. And yes, they say time makes the pain a little bit more tolerable, but you always feel that pain. It doesn't go away, especially with someone like a parent. Why would you want it to? The love that you have for them, that’s the only thing that can surpass death. The memories are the only thing that can cheat time. The stories of them, and their memories.

Mahdis Marzooghian is cofounder and editor-in-chief of Five on the Fifth. She has a master’s degree in professional writing from Towson University, and is a writer and editor based in McLean, Virginia. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in the Miso for Life anthology, Heartwood Literary Magazine, WelterLiterary Journal (print), Mud Season Review, Adirondack Review, BULL Men’s Fiction, Lunch Ticket, Arkana Literary Journal, where her piece won the Editor’s Choice Award, and most recently in Nowruz Journal. Mahdis is the author of debut novel, “Death Has None” (Austin Macauley Publishers, 2023). She is a founding member of the PRWR Towson University Alumni Alliance Writers Retreat program at Still Point, WV.

Other Works

Die Closer to Me

reviewed by Matt Lee

... In the twenty-first century, there are no flying cars or telepods ...

Assimilations

by Dorothy Lune

... I am a king who rules / over my mother’s retired & / mystical ashtrays ...